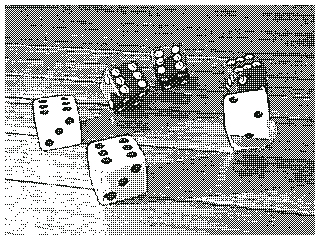

There’s something uniquely terrifying about head injuries. If you’ve broken an arm once, then the next time you’ll know what you’re in for. But when it comes to a bonk on the head… you’ll get a dice roll. And you’ll feel it, too. With an impact to the skull, your brain will jiggle, and a million outcomes are possible.

Amnesia, slurred speech, blurry vision—these are just a few of the potential dangers. But just as there are negative consequences, so too, on rare occasions, have head injuries unlocked a gift. A head injury like a concussion could turn an everyday person into an acquired savant. Acquired savants, also known as accidental savants, are individuals who gain increased intelligence, new senses, or artistic abilities following a traumatic brain injury. On that note, let’s talk about Jason.

A Man Struck By Genius

At age 31, Jason Padgett was a jock and a partier. The muscle man with a mullet had little interest in mathematics. But in 2002, after two men outside a bar bashed him in the head and robbed him, Padgett would get a concussion that would transform his life. That night, he developed OCD, obsessively washing his hands, and he’d go on to develop PTSD, social anxiety, and, most curiously, altered vision.

Padgett had developed a form of synesthesia. It’s a condition in which the brain processes the five senses differently. An example is tactile-emotion synesthesia, where touching certain textures evokes specific emotions in the person with the condition. Padgett’s synesthesia caused him to see mathematical shapes transposed on everyday objects.

Trees, clouds, running water—to Padgett, all were pixelated. Even circles were: the angles were just so small that normal brains smoothed out the edges. With a new geometric view of the world, Padgett fell in love with mathematics. He’d study and soon learn about fractals—shapes within shapes to infinity—and he’d use the impeccable drawing skills gifted to him by his injury to create beautiful, geometric line art. In 2014 he’d publish a book about his experience titled “Struck by Genius.”

Acquired Savants The World Over

Padgett’s story is remarkable, but there are others like him. While their numbers are small, people with acquired savant syndrome come from all walks of life.

Anthony Cicoria was an orthopedic surgeon, but in 1994, at age 42, when a bolt of lightning struck him in the head, his inner pianist awoke, and Cicoria became a composer.

Orlando Serrell was just 10 years old in 1979 when a baseball knocked him unconscious, but once the headaches went away, he gained computer-like recall of every day since his accident.

Diana de Avila was 18 years old when she became a military police officer. But in 1984, a few months after she joined, she got in a motorcycle crash that caused severe head trauma. She would suffer health complications in the decades to come—but also, an awakening as a savant. In 2001, she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, and in 2017, after receiving a dose of steroids to treat her optic neuritis, she experienced a bout of hallucinations and became obsessed with painting. She’d create five or six pieces a day, and now she is an award-winning digital artist.

Leigh Erceg worked on a ranch in northwest Colorado and was more interested in NASCAR than creativity. But things changed after her injury. In 2009, at age 41, she fell into a ravine and her head and spine crashed into the rocks. After her long recovery, she not only began obsessively drawing, writing poetry, and doing advanced mathematics—she also gained a form of synesthesia. Her variant of synesthesia caused her to associate certain colors and shapes with specific colors in the alphabet.

Luck of The Die: Should We Study Savant Syndrome?

These stories are truly astounding, especially considering what it takes for non-savants to reach proficiency, let alone mastery, in any area. To gain skills involves attempts, failures, victories, experimentation, memorization, and time, so much time. But not for savants. Some savants start out their new skill with a level of mastery.

But are the abilities these people receive worth the risk? Acquired savants didn’t ask to get their talents. Whether it’s enhanced memory, synesthesia, or something else, the odds of getting a cognitive enhancement is one in a million. And even if an injured person gains a unique ability, it doesn’t change the fact that they’ve been injured.

After she fell in the ravine, Erceg went through months of recovery, having to relearn how to walk. She also lost a lifetime of memories, including the identity of her mother, and Padgett had to seek therapy for his PTSD and behavioral changes.

Still, it’s undeniably, grippingly fascinating what these people uncovered in themselves that they might never have seen. Despite the many setbacks their injuries caused, Padgett and Erceg both have expressed joy in finding new parts of themselves.

Acquired savants get the lucky side of the die. Through accidents, through shear chance, they emerge from an injury not empty-handed, but with a gift. In the 21st century, a time where neuroscience is on the cutting edge, a question arises: should scientists study acquired savant syndrome in order to reproduce it without causing injuries?

There’s a lot of discourse around using genetics to create children with advanced intelligence or creativity. The goal is to enhance the human race. But one problem with genes is that they’re set in stone once you’re born; no adult alive today would stand to benefit from genetic experiments. Plus, infants can’t consent to having their genes altered or not. The advantage a hypothetical “savant treatment” provides is that it could be performed at any age, and it would be voluntary.

In addition to acquired savants, there are two other forms of savant syndrome. One form is congenital savant syndrome, also known as autistic savant syndrome. These individuals are born with a developmental disability but also have an artistic or intellectual talent.

The other form is a sudden savant syndrome. Discovered by psychiatrist Darold Treffert, sudden savants are everyday people who’ve never had a head injury yet randomly find themselves with a gift, such as being an expert at the piano one day despite never practicing. So far, his research center has only documented 11 cases in the world. Their identities have been kept secret.

With three known types of savant syndrome, there is a lot for scientists to discover about the condition—including how it could be unlocked within a person intentionally. But even if it’d be more advantageous than genetic enhancements, there’s an ethical question to ask as well.

There’s a high probability that privileged classes would get access to a “savant treatment” before everyone else. And who knows what selfish, egregious acts they would commit with enhanced intelligence or other abilities. In an ideal world, everyone would have the choice and access to enhance themselves or not, and there’d be no discrimination between those who do and do not.

I don’t believe we live in that ideal world, but I still want to dream. About what things could be like. Imagine the feats of creativity that would be possible, or the ability to switch on and off different forms of synesthesia. Imagine everyone having a high level of intelligence and using it to better society.

Whether or not this is achieved, a question remains: what exactly causes acquired savant syndrome? Why doesn’t every head injury lead to it? Let’s examine what happens to the brain following a concussion to see if any of the effects are related to savant syndrome.

The Inner Workings of The Brain’s Connectivity

The brain never gets a day off. It is always taking in and processing information from the outside world, and from the inside of your body. Concussions disrupt this flow. When the brain jiggles in the skull, short-term or permanent damage may occur.

A variety of, physical changes might be seen, including brain swelling, bruises, and bleeding. But sometimes, the changes are harder to detect.

In her May 9th, 2023 article for Live Science, titled Even mild concussions can ‘rewire’ the brain, possibly causing long-term symptoms, Anna Deming noted: “even mild traumatic brain injuries that don’t cause any observable structural damage can still trigger symptoms that persist for more than six months. These symptoms range from problems with concentration and fatigue to depression and anxiety.”

Structural changes to the brain aren’t always apparent in concussion victims—this applies to acquired savants as well. To MRI and to CT scans, the brain may appear normal. But it is with fMRI scans that changes in the brain’s connectivity can be detected.

Rebecca Woodrow, PhD student at University of Cambridge’s Division of Anesthesia, was the first to make this discovery. The details can be found in her August 2023 journal article, Acute thalamic connectivity precedes chronic post-concussive symptoms in mild traumatic brain injury. During the course of the study, which ran from the early to late 2010s, Woodrow and her team found traumatic brain injuries spur a significant increase in connections with the thalamus and the rest of the brain.

The thalamus acts as the brain’s relay center: all sensory information like sight or smell must pass through it before being transmitted to its proper channel. The thalamus also processes complex info that relies on multiple brain regions at once, like the ability of concentration.

According to Woodrow’s hypothesis, parts of the brain become hyperconnected with the thalamus in order to adapt to the injury. Another theory she posited is that the thalamus could be responding to its own injury, rather than the injury of a separate brain area.

According to Deming of Live Science, some scientists believe that after the brain becomes hyperconnected, connections throughout the brain dwindle and become lower than usual, for a long-term period. But prior to the connections dwindling, the hyperconnected regions can predict what type of symptoms a traumatic brain injury victim will undergo.

Woodrow and her team found that whatever symptom patients went through—whether emotional changes or cognitive changes—correlated with the brain region or regions that were hyperconnected. Neurotransmitter levels in these areas were also affected, and Woodrow’s team believes studying these altered neurotransmitters could lead to new treatment methods for traumatic brain injuries.

So, what causes acquired savant syndrome? While there is no definitive answer, it’s possible it’s caused by the rewiring and hyperconnectivity that occurs between the thalamus and certain brain regions. Everyone’s brain is different, and everyone recovers from head injuries differently. There is still more for scientists to discover, but as they improve at understanding the brain, they will get closer to an answer.

In fact, there have been several scientists in the 21st century, like Allan Snyder or Berit Brogaard, who’ve created theories on how savant syndrome could be unlocked intentionally. One idea is that the left anterior temporal lobe is responsible. In studies Snyder has conducted, magnetically suppressing the LATL of neurotypical individuals causes them to temporarily become better artists or be able to solve difficult puzzles.

Stay tuned for a future article where I discuss more of these theories.

A Door to A New You

If Padgett and the other savants have taught us anything, it’s that all the secrets to ourselves live inside of us. The secrets to who we are. The secrets to who we could be. Secrets we might never have imagined. More creative. More intelligent. More curious. Ecstatic to perform a hobby we previously never had. All it takes is for something to unlock it. While the savants listed here have had that door unlocked by accident, one day, we could unlock that door with intention.

What do you think of savant syndrome? Do you think we’ll make any major breakthroughs this century? If you could ask someone who had this condition one question, what would it be?

Leave a comment